Note: These assumptions are now outdated. Our current capital market assumptions and our white paper documenting their construction can always be found on our Capital Market Assumptions page.

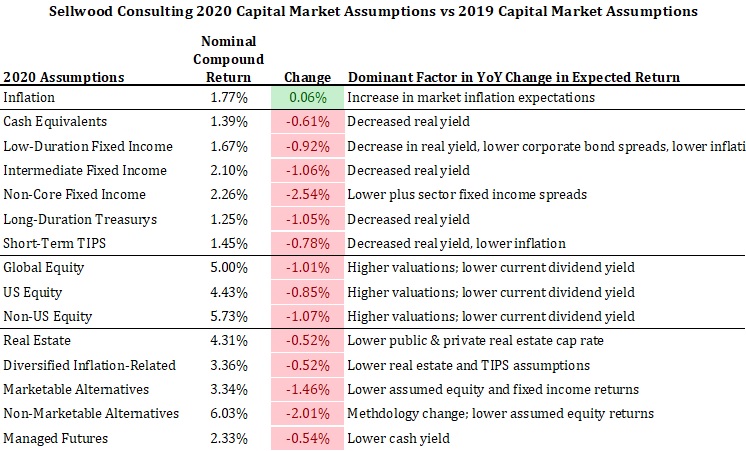

Sellwood Consulting’s 2020 Capital Market Assumptions contemplate a prospective lower-return environment caused by last year’s extraordinary valuation expansion in nearly every asset category.

These 10-year, forward-looking assumptions of asset class return, risk, and correlation are the key input variables for our asset allocation work on behalf of clients.

2019 Was Extraordinary but Borrowed from the Future

Over the course of 2019, every major asset class became more expensive. Expensive equities became more expensive, and low-yielding bonds saw their yields decline. Most of the extraordinary returns that we witnessed in 2019 borrowed from future return, and our forward-looking assumptions declined accordingly.

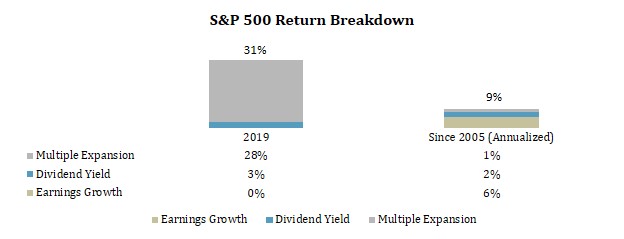

We can consider one example: U.S. large company stocks. In 2019, the S&P 500 returned 31%. Less than 3% of that return came from dividends. Underlying earnings stayed flat for the year, contributing less than 1% to total returns, as corporate performance stagnated. Over 90% of the index’s return – 28% — came from simple multiple expansion, reflecting the fact that investors were willing to pay 1/3 more for a dollar of future earnings at the end of the year than they were at the beginning of the year. (This effect was especially pronounced for growth stocks, where cash flows are further into the future, as the Federal Reserve reduced discount rates and made those future cash flows more valuable in the present day.)

Over the long-term, stock returns are driven by earnings growth, which is either reinvested or returned to shareholders in the form of dividend payments. When asset prices go up because of valuation expansion, as opposed to fundamental growth in the underlying asset, these prices borrow from future return.

Long-term equity valuations are higher today than they have been at any time in history, with the notable exception of the 2000-2002 equity market bubble. Our process soberly assumes that valuations will not remain at these elevated levels, reverting instead toward a long-term average. In the case of U.S. Equities, this analysis subtracts nearly three percentage points from our assumed future annual return over the next decade — or about 30% in total. Essentially, in the case of U.S. Equities, we assume that 2019’s equity market revaluation is reversed over the next decade. Over the long term, it may very well be the case that higher valuations are warranted. But if all of that repricing occurs in a single year, by definition it cannot happen again. We don’t know what the market’s valuation multiple will be in 10 years. But whatever it is, higher valuations today present a shallower path of return from here to there.

Bonds are a simpler story, but our analysis is similar. Like with equities, we assume bond valuations — real yields — will revert toward a historic norm over the coming decade. This analysis implies that 2019’s stellar performance for bonds, which was entirely based on yields falling, will be partially reversed in the next decade. In the simplest possible terms, when bond yields decline, an investor experiences future potential return accelerated into the present. The lower yield you end up with implies that returns will be lower in the future – they must be, because you have already experienced part of your total return. Owning a bond (or bond portfolio) as yields decline means, quite literally, that you have pulled return from the future into the present — borrowed from future return.

This is not a bad problem to have, if you own the asset — who wouldn’t want their cake sooner? It only presents a challenge for allocating portfolios for the future. Our 2020 assumptions acknowledge 2019’s extraordinary market returns by presenting a rather dismal forecast of the next decade:

Last Year: Right Direction, Wrong Horizon

It may be worth noting that when we developed Sellwood’s 2019 Capital Market Assumptions a year ago, we painted a much rosier picture. Following a dismal year for stocks and bonds, we stated, “we believe that over the next ten years, investors will receive more compensation for taking risk than they were poised to a year ago. In the case of fixed income, higher real yields bring greater opportunity for return with lower risk. For risky assets, like global equities, the market experience of 2018 brought lower valuations, which increase the potential for future return.” Our analysis proved correct — but the entire benefit that we forecasted over the next decade happened to occur in the first year of the forecast period.

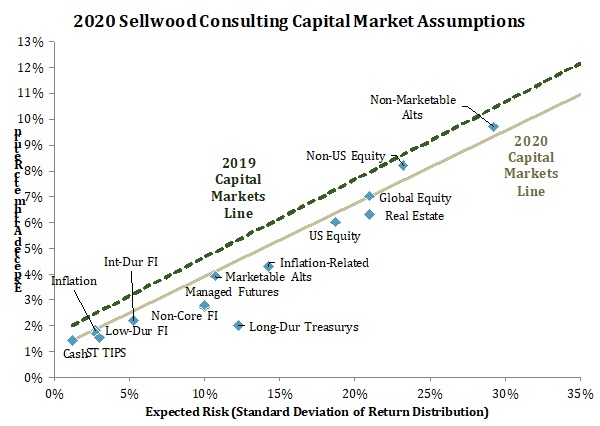

As a result of these updates, our 2020 forecasted “capital markets line,” depicting opportunities for investment return at varying levels of risk, has declined. It is perhaps interesting that the line has not flattened — generally speaking, after a 30% year for stocks, their expected return would decline, flattening the line. But today, following extraordinary returns for both stocks and bonds, the entire line has shifted down in parallel (from the dotted line to the tan line):

Portfolio Implications

The height of the capital markets line determines the level of return that an investor can expect, over the long term, by investing in various combinations of assets. Over the last year, higher valuations in every asset class have pushed this line downward. Investors should expect lower returns from today’s starting point than from the more generous starting point that markets offered a year ago.

The slope of the capital markets line determines how much an investor can expect to be compensated for taking risk. That the slope of the capital markets line hasn’t meaningfully changed this year suggests that market movements in 2019 did not present any meaningful new relative opportunities between asset classes.

Where does all this leave us? With an uninspiring set of market opportunities. At minimum, we suggest that investors should be careful about extrapolating past returns – especially recent past returns – into the future. If those returns have borrowed from the future, they won’t be repeated.

Investors with fixed liabilities that require a specific investment return (e.g., many endowments, foundations, and underfunded pensions) face a very difficult asset allocation environment. Lower return opportunities in capital markets coupled with fixed return objectives imply that more portfolio risk must be taken to achieve the fixed return objective. Increasing risk at a time when valuations are high leaves little room for error.

Markets today aren’t offering many places to hide, but investors’ unique circumstances might. If we can offer any solace to the dim outlook we have presented, it is to suggest that long-term investors can take refuge in those long-term horizons. Investors that are truly structured for the long term can still reasonably expect that equity risk will be rewarded, that bonds will diversify their portfolios, and that reasonable liabilities can be met with investment return.

Even after this year’s changes, we still forecast annualized compound returns of 4.5-5.5% for most diversified portfolios, over the coming decade. The future won’t repeat the past, but it will still probably be all right.