Back in 2014, we wrote a piece, Who’s Afraid of the Big Bad Rates?, which argued that long-term investors in fixed income securities should not fear rising rates.

At the time, we argued two things — first, that it is not the question of whether rates would rise, but rather the timing and pattern of their rise, that determines how harmful rising rates are to a bond investor. Second, we suggested that of all the reasons for rates to rise, investors should not fear rates rising because of Federal Reserve actions – because the gradual nature of typical Fed interest rate movements gives rise to bond returns that are essentially unaffected by the rate movement. Rising rates are a double-edged sword, slicing principal value from bonds already owned, while paying higher coupons on those not yet purchased. It is possible, we showed in 2014, that rising rates could actually turn out to be a good thing for bond investors.

While all of that logic remains true, the world for bond investors is a different one than it was four years ago. Unlike in 2014, rates are rising today, because of strong economic growth, a tight labor market, concerns for potential inflation in the future, and an articulated long-term, careful reversal of the Fed’s stimulative monetary policies that have kept rates low for the last nine years.

The world is different today, and rates are (finally) actually rising. Is it different enough that investors should now fear rising rates?

What’s to Fear?

“Aggregate” bonds are those issued by US-based investment-grade issuers, including the US Treasury, agencies, and corporations. They are intermediate-term in nature and have a current duration of 6.1 years. They are a reasonable proxy for the types of bonds typically held by many long-term investors.

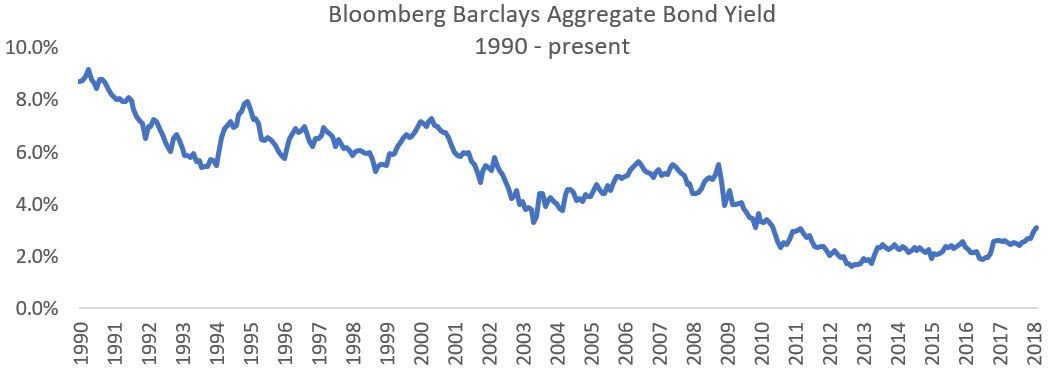

For a variety of good reasons, Aggregate bonds currently yield less than their long-term average: as represented by the Bloomberg Barclays Aggregate Bond Index, Aggregate bonds currently (as of February 28, 2018) yield 3.1%, whereas since 1990, their average yield has been 4.8%. Fears of their rates rising in the future are well founded. What happens to bond portfolios if rates continue to rise?

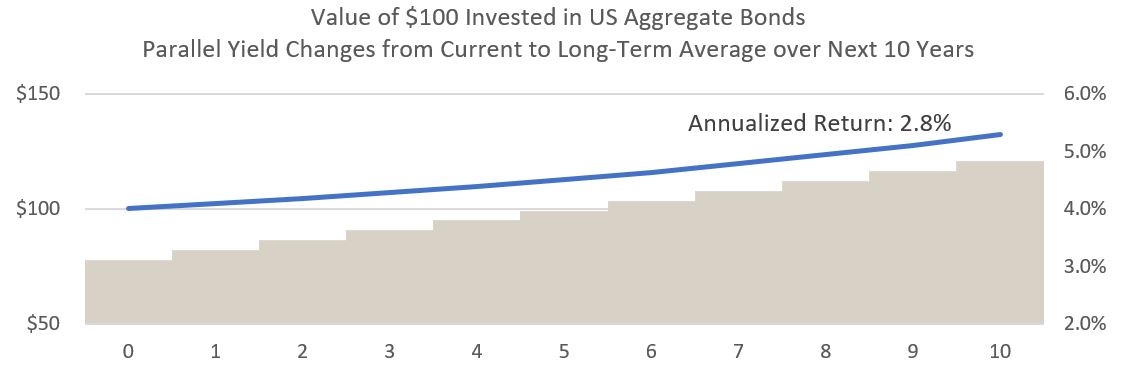

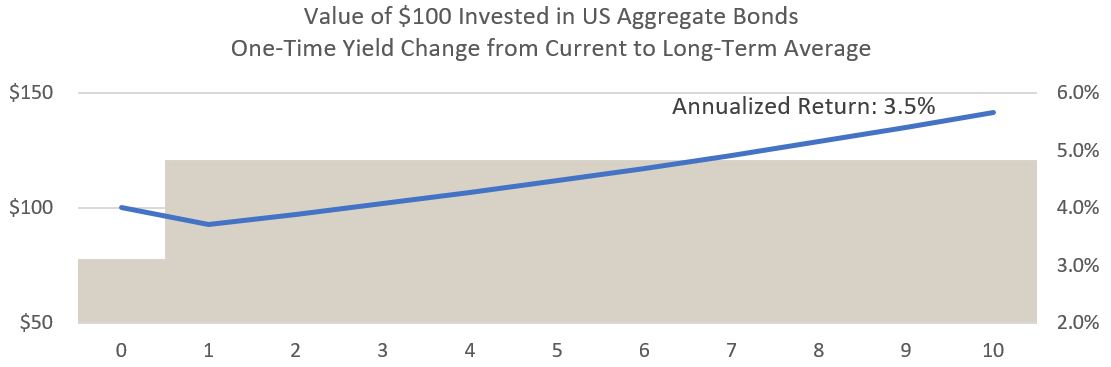

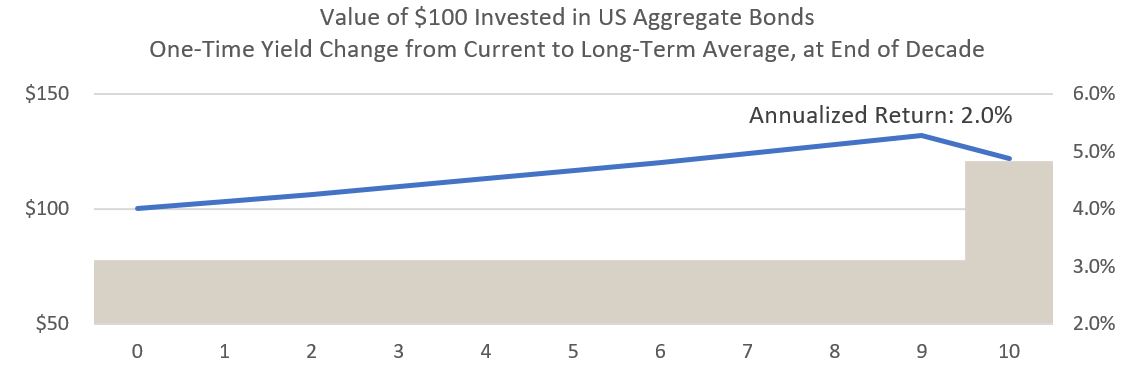

We have modeled several scenarios for future Aggregate bond portfolio returns, given different paths of rising interest rates. In each chart below, the tan bars represent the hypothetical future yield of an Aggregate bond portfolio, and the blue line represents the growth of $100 invested in the portfolio over the next ten years. Yields are plotted on the right axis, and value of the initial $100 is plotted on the left.

It may go without saying, but it bears repeating: the expected return for a bond portfolio is its current yield. If rates do not change over the next 10 years, we expect a portfolio of Aggregate bonds to return 3.1% per year over the decade. This is the base case return, against which we can compare several alternate scenarios.

Scenario #1: Rates Gradually Rise to Their Long-term Average

The following chart depicts the value of $100 invested in an Aggregate bond portfolio over the next 10 years, if the portfolio’s yield moves from its current level, 3.1%, to its long-term average, 4.8%, in even annual increments over the next ten years.

Under this scenario, the annualized return for the decade is 2.8%, which is 0.30% per year lower than the current yield. If rates rise in this fashion, holding all else equal, investors will earn 90% of the return they would have had rates not changed at all. Hardly a disaster.

Scenario #2: Rates Rise Quickly to Their Long-Term Average

What about a scarier scenario – that instead of yields rising monotonically to the long-term average in every year, they spike immediately in the first year, returning to their long-term average, and then never change again?

This scenario is even better for the investor than the first: after a one-time drawdown, of about 7% of initial portfolio value, the bond portfolio recovers, and its total return returns to positive territory in the third year. The reason is that higher rates pay higher income – enough to offset a principal drawdown after less than two years, and in every year thereafter. The total annualized return over the decade is 3.5%, significantly higher than the portfolio’s starting yield. Far from being a scenario to fear, this is the type of rising rate scenario that long-term investors should root for.

Scenario #3: Rates Rise to Their Long-Term Average, 9 Years from Now

At the other end of the thought-experiment spectrum, we can design the opposite scenario: one where rates don’t change at all for nine years, and then spike to their long-term average in the final year:

This scenario combines the worst of both worlds – low coupon income for most of the decade, followed by a principal drawdown at its end due to the sudden rise in rates. Still, this worst case of our three scenarios results in a positive annualized return of 2.0% over the decade – a disappointing outcome relative to expectations, but far from a devastating one.

Holding all other variables constant and focusing solely on interest rate movement, these three scenarios represent bookends for future Aggregate bond returns. Under these assumptions, we cannot engineer a scenario where Aggregate bond returns will be painful over the coming decade. If we accept that interest rates are low and have potential to rise, but only as high as their long-term average, their annualized returns over the next decade will be somewhere between 2.0% and 3.5% — somewhere between 65% and 112% of the return you’d expect if rates didn’t change at all (3.1%, the current yield).

The gravitational pull of current yields is strong and nearly inescapable– it is very likely that future returns will be close to it. Any scenario less dramatic than those depicted above will result in an annualized return for Aggregate bonds, all else equal, closer to their current yield of 3.1%.

What Would It Take To See Negative Returns?

We have seen that it is very difficult to engineer a path of rising interest rates that would generate disappointing returns, as long as we assume that rates will rise no farther than their long-term average.

But what if we relax that latter assumption? It is possible, after all, that a regime change for bond yields lies just over the horizon, and that an extended period of below-average rates will be followed by a period of above-average rates.

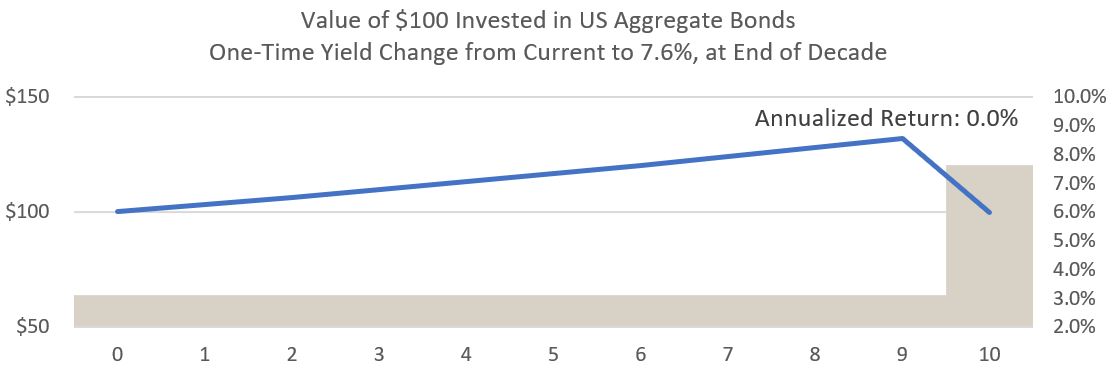

How high would rates have to rise to generate zero bond returns for an investor, over a 10-year period? A scenario where rates don’t change for 9 years, and then rise by 4.5% in the final year of the decade, would do it:

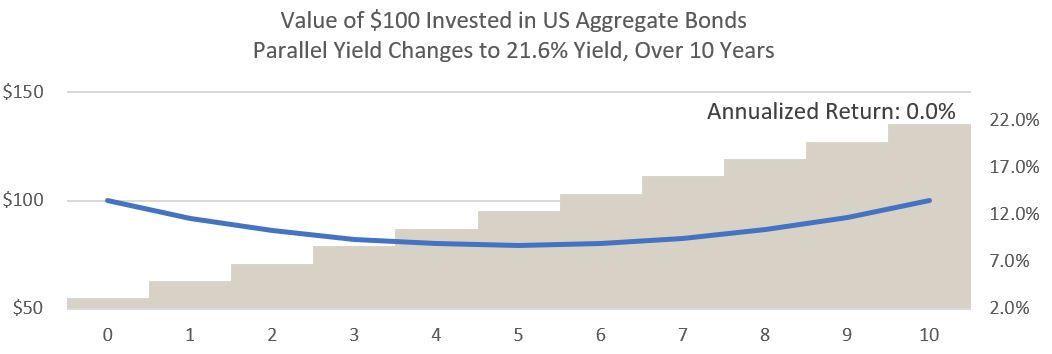

So would a scenario where bond yields rise every year by 1.85% — for a total of 18.5 percentage points over a 10-year period (from a yield of 3.1% to a yield of 21.6%):

This is what it would take for Aggregate bonds to deliver a flat return over the next ten years: either rates need to gradually rise to historically unprecedented levels (the highest recorded yield for the Bloomberg Barclays Aggregate Index was 15.4%, in 1981) or yields need to actually not rise at all anytime soon, until they more than double in a single year, nine years from now. How likely are these scenarios?

If these scenarios are unlikely, any predictions for a meaningfully negative Aggregate bond returns over the next ten years are downright outlandish. These “disappointing” returns we have constructed are merely 0% annualized returns over a 10-year period. It would take significantly more heroic assumptions to forecast meaningfully negative returns for Aggregate bonds. As well, any such scenario we could design would build in such high yields at the end of the 10-year period that subsequent bond returns would be phenomenal, benefiting from very high yields (coupon payments) at the end of our ten-year forecast period and the beginning of the next. Under this extremely unlikely scenario, any loss in the coming decade would be quickly recovered shortly thereafter.

Nothing to Fear but Fear Itself

All of our modeling has made a critical assumption that investors are long-term investors, with relevant investment horizons of at least a decade. We are comfortable making this assumption because investors with shorter horizons than a decade probably should not have all of their bond investments in Aggregate bonds anyway. Investors with shorter horizons should own shorter bonds, which are less exposed to interest rate movements. Investment horizon is among the most relevant questions to ask when designing a portfolio.

Over long enough horizons, most risks melt away, and interest rate (duration) risk is no exception. The ability to ignore short-term market forces is one distinct advantage of being a long-term investor. Most of the damage that an intermediate duration bond investor can suffer from a rapid rise in interest rates is a result of either choosing to or being forced to sell shortly after a significant rise in interest rates. If an investor can hold onto the bonds for the longer term, higher coupons will recover the early losses over time – but only if the investor doesn’t sell them first.

We caution any investor against the temptation to modify a long-term portfolio away from its optimal allocation, which should ideally be designed specifically for that investor and its unique circumstances, in response to predictions for short-term market forces. This includes any predictions for the direction of interest rates. All forecasts, including those for interest rate direction, are unreliable. Even the US government hasn’t demonstrated any ability to forecast US government bond interest rates.

Equally, we maintain ourselves, and counsel our clients to maintain, humility in the investment process. While it’s always possible that this time is different, and interest rates could go from 3% to 21% over the next decade, it is very unlikely. It would take an unprecedented circumstance for a bond investor to experience a truly disappointing return. While every risk is worth hedging, very unlikely risks are worth hedging only at the margin, not by dramatically changing either the size or composition of a bond allocation within a diversified portfolio.

Finally, we encourage all investors to do the math. The above modeling is available to anyone with a finance textbook and a calculator. We did not invent it. Every scenario we have modeled acknowledges a possibility for higher rates – in fact, every scenario assumes rising rates. But assuming rising rates is not enough – the path and magnitude of the rising rates are much more consequential than a prediction of whether they will rise. The above analysis shows that some reasonably likely scenarios for rising rates actually benefit the investor.

Ultimately, when we look at bonds, it is difficult for us to see a scenario where long-term investors will be disappointed relative to reasonable expectations – you have to torture the data pretty thoroughly to get it to confess to prospects for disappointing return. Very few portfolios are made up entirely of bonds. They typically exist in a portfolio to offset other risks – mainly, those delivered by equities. This important portfolio role for bonds is far from nullified in the face of prospects for rising rates.